A decade after the Norman invasion of Britain it was King Caradog who was sole ruler by 1077 and warded off Norman intervention by paying tribute to William the Conqueror.

It allowed Caradog the freedom to war with Rhys ap Tewdwr, King of Deheuabrth and he fell in the battle in 1081. Following Caradog’s death it brought William the Bastard swiftly to the scene to overpower Rhys from taking over the kingdom and stamp his authority on south wales. No welsh king continued in the area and William became overlord of Caradog’s kingdom which was divided amongst a number of nobles.

Glamorgan, or Morgannwg, was originally an early medieval kingdom of varying boundaries known as Glywysing. Although initially a rural and pastoral area of little value, the area was a conflict point between the Norman Marcher lords and the Welsh princes, with the area being defined by a large concentration of castles.

The last of the Glamorgan Welsh Lords was Iestyn ap Gwrgan (1040-1091) who saw the kingdom fall into Norman hands following the assault of Robert Fitz Hamon (1042-1107), 1st Earl of Gloucester and Lord of Glamorgan. The precise details of the Norman conquest of Glamorgan, and how much Iestyn was able to organise is not known but he is presumed to have been killed at the hands of Fitz Hamon.

Iestyn ap Gwrgan, was the great grandson of King Morgan Hen who ruled the country between the Tawe and the Taff. We can safely assume Llantrisant was a settlement at this time. We know Iestyn owned an estate called Villa Milue in the Garth Maelog Estate which he granted to Brishop Herwld in 1093. Iestyn may well have been governor under King Caradog.

Robert Fitzhamon attacked South Wales in around 1091. He ordered the construction of a motte (mound) and wooden bailey (keep) in the middle of the dilapidated Roman castrum in Cardiff. Once Fitz Hamon had control of he allowed the remaining Welsh Lords to manage the surrounding mountainous region. The arrival of Fitzhamon saw the first Anglo-Norman Lordship of Glamorgan, one of the most powerful and wealthy of the Welsh Marcher Lordships. Like all Marcher lords, he ruled his lands directly by his own law: thus he could, amongst other things, declare war, raise taxes, establish courts and markets and build castles as he wished, without reference to the Crown.

The Lordship was split after it was conquered; the kingdom had the town of Cardiff as capital and took in the lands from the River Tawe to the River Rhymney. The Lordship also took in four of the Welsh cantrefi - Gorfynydd, Penychen, Senghenydd and Gwynllwg. The lowlands of the Lordship of Glamorgan were manorialized, while much of the sparsely populated uplands were left under Welsh control until the late 13th century.

Further change came with the death of Rhys ap Tewrdwr in 1093 in the battle against the Normans invading Brecon. Robert Fitzhamon presumably took the opportunity to extend his power and take the vale area as far as the Ogmore River. Probably Iestyn ap Gwrgan paid homage to him, rather than an actual conquest.

Llantrisant had such a strategic position without which it would have been difficult to hold the lower Ely valley in peace and without doubt it had some presence at this point. At this time the Bishop Urban reigned from 1107 to 1134, He was a Welshman and creator of the Diocese of Llandaff and builder of the first Norman cathedral beside the Taff. Could he possibly be the man behind the creation of the huge parish of Llantriant out of an original foundation? Could he have persuaded the Norman overlord to build a fine Romanesque church just as he was doing at Llandaff?

Fitzhamon died in 1107 and the title was handed to his daughter, Mabel Fitzhamon who married Robert Fitzroy (Robert Consul), 1st Earl of Gloucester (c 1100-1147), the eldest illegitimate son of King Henry I of England. There is no evidence to suggest he was challenged during his reign of Glamorgan from 1107-1147.

Earl Robert acquired the lowlands but Caradog ap Iestyn was in control of the area north of Llantrisant. A Welsh counter attack was unleashed in December 1135 on the death of Henry I but we have no evidence of this affecting Llantrisant. We can only assume that at the time sporadic warfare was the norm.

The title of Earl of Gloucester and Lord of Glamorgan was later passed to his son, William Fitz Robert (1147-1183) and finally to his daughter, Isabel, (c. 1173-1217). Although married twice (firstly to Prince John, the youngest son of Henry II) she died childless.

By 1211 Welsh leadership was still in control with Hywel ap Maredudd and Morgan ap Cadwallon in charge of Meisgyn and Glynrhondda. When Gilbert de Clare captured Morgan it left Hywel ap Maredudd of Meisgyn leader of the Welsh in Glamorgan. He took Glynrhondda, and attached the area of St Nicholas, St Hilary and Kenfig by 1229.

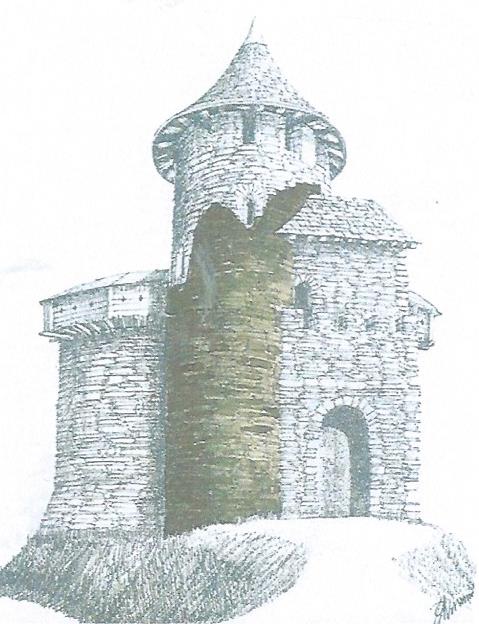

Llywelyn ap Iorwerth, Prince of Gwynedd, held the lordship of Brecon at this time and probably gave his support to independent lords of Glamorgan whose firm allegiance he received. When he died in 1240 his son was unable to exert the same influence and the young Richard de Clare took control. Drastic action took place with the building of his administrative centre in a castle at Llantrisant in 1246.

With thanks to J. Barry Davies, author of “The Five Hamlets of Llantrisant” and “The Freedom & Ancient Borough of Llantrisant”.