During the Middle Ages the vast majority of the population had no access to any kind of education.

During the Middle Ages the vast majority of the population had no access to any kind of education.

Only the sons of the property owning classes could afford to attend the few schools which did exist and go on to Oxford or Cambridge, or enter the Church or the legal profession.

By the 16th century the expanding trading classes wanted an education for their sons and a number of grammar schools were set up to meet the new demand, some created like Christ's College, Brecon, by the church, and some, like John Beddoes' school in Presteigne, endowed by successful local businessmen.

During the period of the rule of Parliament following the death of Charles 1, attempts were made to create a system of education open to a wider section of society and sixty "free schools" were founded in Wales. Although little is known about these schools and they were swept away at the Restoration of the monarchy, they did demonstrate new possibilities. Thomas Gouge of London established a fund in 1674 to help set up Welsh language schools across Wales which taught basic literacy through the Bible and religious texts according to Anglican principles. He also created the Welsh Trust to publish books in support of these aims. Some 300 schools were created in this way.

In 1699 four men including Cardiganshire MP, Sir Humphrey Mackworth, the Neath industrialist established the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, which set up a nationwide network of Anglican charity schools across Wales. Teaching was in both English and Welsh and the SPCK published and made widely available a Welsh Bible. As well as basic literacy and the catechism, boys were taught arithmetic and girls needlework, spinning and weaving. Although the schools were set up in a wide variety of buildings, annual inspections kept the standards to a high level.

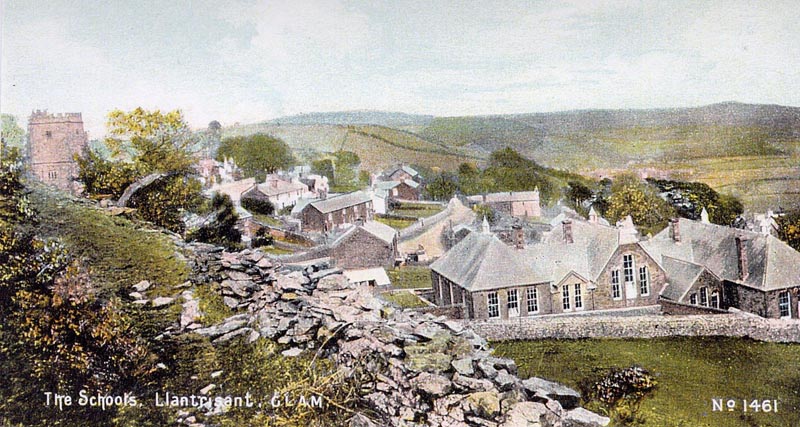

If Sir Humphrey was the leading supporter of the society in the county, its chief clerical supporter was Rev James Harris, vicar of Llantrisant, prebendary of Llandaff and fellow of Jesus College, Oxford. He founded the society’s first two charity schools in Wales in 1699 and worked unremittingly for the society until his death in 1728. In 1701 he established two Charity Schools in Llantrisant and by 1716 had 30 pupils on the roll in a town were parishioners were “lazy and mutinous” and “addicted to sports, even in divine service”, so he became “forced to restrain them” against atheism. They were conducted by the curate whom Harris kept for this purpose. Rev Harris actually founded the last SPCK school in Glamorgan at Llanwynno in 1724 and the society’s records reveal that the number of children had by then increased in Llantrisant.

From 1739 to 1773 a circulating school of teachers held classes in Guildhall and Corn Market, patronised by Lord Bute. By 1800 there were three charity schools in Llantrisant, but the system was deplorable. Flogging of boys was widespread, work was ill-prepared and children were insubordinate. One was condemned for “drawing ludicrous figures on the slate and showing them to the boys.”

As early as 1811 there had been a meeting at Bridgend of all clergy in the Llandaff diocese and by 1812 moves were made to enter “into union” with the National Society and a number of church schools were founded. They were not purpose built and many were held in dilapidated buildings. Demand for the National Schools in Wales outstripped supply which caused problems of overcrowding and stretched the financial commitment of the National Society to exhaustion. The local committees were responsible for maintaining the buildings, paying teachers and such costs were raised through collection, subscription or payments by parents.

At Llantrisant the National School was able to build on the work begun by Griffith Jones’s Circulating Schools who worked in the parish several times. and those of the SPCK. Teaching was largely confined to moral and religious topics, domestic crafts, arithmetic, reading and writing. One teacher instructed a group of monitors (boys of ten or eleven years of age) and they imparted their knowledge to small children in the schoolroom. There were obviously severe limitations on the depth of knowledge that these monitors could retain and its effectiveness was questionable.

The surviving letters begin with Richard Fowler Rickards thanking his lordship for the honour of being entrusted with ‘organising the Llantrisant school’.

Fear of revolution in the years following the Napoleonic wars had prompted the national conscience into serious moves towards introducing education for the poor. From 1811 two great voluntary societies had been established; the National Society for the Education of the Labouring Poor in accordance with the Principles of the Church of England and the competing Free Church British and Foreign Bible Society and both were highly successful in establishing National and British Schools throughout England and Wales. It is worth considering the local background to this.